The ACC is the Marginal Conference in Football Centric College Sports World

26 of 32 First Round NFL Picks hailed from the SEC & Big10; Texas to spend $40 Million on football alone

Football is where the money is in college sports. Two recent data points:

26 of the 32 first round picks in this week’s NFL draft came from the SEC and the Big10 and football is where the money in college sports resides.

Ohio State (Big10, that has 18 members) is said to have spent $20 Million on its football roster last season, with word today that the University of Texas (SEC) plans to spend $40 Million on its football team in 2025.

Both the SEC and Big10 are all in on football and the Big12 wants to be. The ACC has to be from a financial standpoint, but men’s basketball is the crown jewel of the conference. Can universities like Duke and UNC, who together have made 39 appearances in the men’s basketball final four manage to live in the big football money world while being more interested in basketball success? I suspect the answer will be yes and the post will work through why and how. These two ACC arch rivals, along with Kentucky are said to have a $10 Million annual NIL budget to spend on men’s basketball (disclosure: I have three degrees from UNC and have been a professor at Duke for 28 years, and I am a huge sports fan).

The revenue sharing at the heart of the House v. NCAA settlement is 75% for football, 20% for men’s basketball and 5% for everything else. This lines up with it cost $40 Million to be at the top of the football NIL market, with it being less for men’s basketball ($10 Million).

The key sticking point in settlement negotiations is a hard cap on roster size of all sports, with no limits on the amount of scholarship up to the cost of attendance that universities can provide to athletes. At issue is the relatively large number of players on teams today who will not be allowed to continue participating beginning in the fall (football walk-ons and non-revenue sports players will be most affected), and the reality that universities can no longer say they are unable to pay full scholarships for non-revenue sports—that will become a choice. This seems likely to be worked out with a ‘grandfathering’ of sorts, and so is mostly a sideshow. The financial numbers for revenue sharing are set, but with one huge policy decision yet to be made.

The most important policy issue remaining to be solved is how the power conferences will regulate third-party payments of NIL money to players, above the direct payment from universities to players that is capped at $20.5 Million per year for the 2025-26 academic year.

How Can Texas Plan to Pay $40 Million if the Revenue Sharing Cap is $20.5 Million?

How can Texas plan to spend $40 Million—double the so-called revenue sharing cap— beginning during this next academic year? The answer is that the $20.5 Million only caps what universities can directly pay to players under revenue sharing. Players can also be paid directly by third parties that are—I am not sure what to call them. They are not controlled by the university, but they exist for the benefit of the university’s athletic program by arranging for Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) payments to players. And they arrange spending in consultation with the university’s athletic department (Here, the Texas Athletic Director is openly discussing this). Let’s call them “Booster clubs that arrange payments for players” (BCAPP’s).

How will BCAPPs be regulated? An ESPN article described the goal of the regulation process in early April, 2025 to be:

To help keep wealthier teams from using boosters or NIL collectives to gain an advantage by exceeding the cap, the NCAA's power conferences are creating a clearinghouse, separate from the NCAA, to approve future NIL deals between players and boosters. The House settlement states that athletes have to report any NIL deal they sign with a third party that is worth more than $600 and that any such deal has to be for a "valid business purpose."

Acceptable deals, deemed "real NIL," can range from a national advertising campaign for, say USC women's basketball star JuJu Watkins, to a three-figure appearance fee at a local car dealer for a lesser known athlete.

The power conferences have contracted with auditing giant Deloitte to review booster NIL deals and decide whether each is a legitimate endorsement contract or a veiled attempt to circumvent the salary cap.

Quaint.

I don’t know if things have already changed that much in a month, or if the above piece was hopelessly unrealistic, but universities are explicitly spending more than the cap via BCAPPs—double in the case of the University of Texas on football alone. The details of the Deloitte-run clearinghouse to determine if NIL deals funneled through BCAPPs are “real NIL” have yet to be finalized. The point appears to be to ensure that said deals are “legitimate, market-determined” deals that are based on the value that an athlete provides to a sponsor.

I can imagine all sorts of ways of doing this, and could probably enjoy geeking out on devising such a system. Keep in mind that the highest paid NIL player in college sports is Arch Manning, a quarterback at the University of Texas, who has barely played during his college career. See below for his stats as a dual threat Quarterback who can run and pass. (Based on his QB RTG of 184 as a back up in 2024, maybe he should have played more).

Arch Manning is an unusual case due to his famous grandfather (Archie Manning) and Uncles (Peyton and Eli) and could be viewed as a one-off:

Bohls added that Arch Manning is "by far the highest-paid Texas player," but none of his money comes from the school because "he and his family acquired all his deals on their own 'with no help from the school.'"

From this quote, it is unclear whether Arch Manning’s $6.6 Million estimated NIL even ran through the BPACC that supports the Longhorn athletics department or if it went directly to him if “his family arranged it” without help of the University. Presumably, it will have to be run through and “judged” by the Deloitte-run clearinghouse beginning this coming academic year (all deals greater than $600 are to be so-approved). And they will have to say that it is—something. Legitimate, market based, not illegal, of appropriate value? I am really not sure exactly what Deloitte will be judging, but a group with power to do something that has an unclear goal is not a great start. However, Arch Manning being the highest paid player via NIL payments without demonstrating sustained on field success seems to nudge the standard toward whatever someone is willing to pay.

The Athletic Director at the University of Texas says in this piece that he thinks the spending this fall will be a one-time thing and that once the ‘salary cap’ process gets in place there will not be escalation of spending. He seems to imply spending will fall back toward the revenue-sharing cap. I do not think that he is joking, but let me just say I bet him a steak that does not turn out to be the case, and the cost escalation will be continue unless stopped. And given these are market transactions, it seems hard to determine the basis on which to stop them.

The ACC as the Marginal Conference—Can Basketball Focused Schools Make This Work?

I think probably yes.

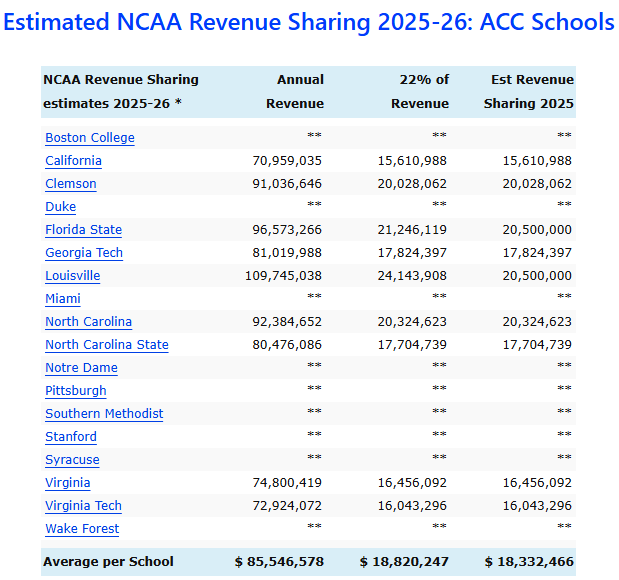

The ACC is the marginal conference—huge basketball names locked into a football-driven sports world. Below is the estimated revenue-sharing amount for the coming academic year for the ACC. Only public universities must report this information but one thing to note is that based on existing television and media contracts, only Florida State and Louisville are up against the cap of $20.5 Million that they can directly provide to players. Clemson and UNC are close. Schools can spend more than their estimated revenue amount (if your cap calculation comes in at $19 Million, you can still spend $20.5 Million), but they do not have to do so. And any revenues from an individual university’s BPACC that sets up NIL for players is in addition to the $20.5 Million cap—the money from the existing BPACCs do not appear in the tables below.

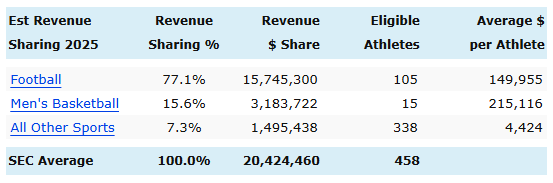

Below are the estimated payments from ACC schools for revenue sharing by sport and player/sport; I am unsure if the below includes private universities or not. However, the point I want to make is that there are some fairly sensitive market-driven subtleties to the system of sharing revenue agreed to as part of the settlement.

Football teams have a large number of players, so more money spread across more people has a lower per athlete share ($127,000 v. $249,000 for men’s basketball in the ACC). Note that universities do not have to pay teams based on an average, this is descriptive.

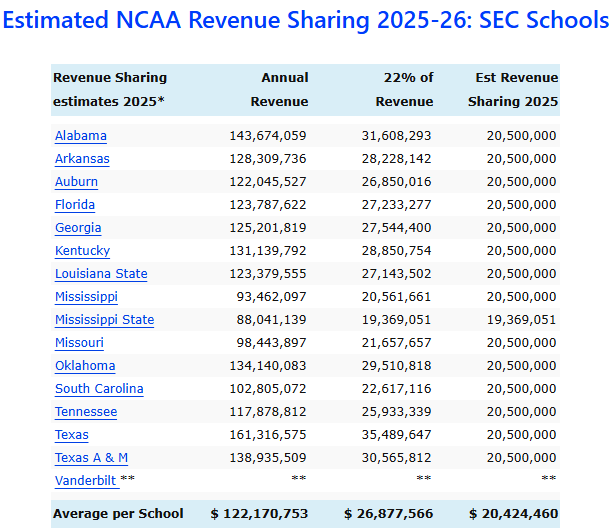

In the SEC, only Mississippi State is not pushed against the $20.5 Million cap, due to the lucrative nature of their football television and media package. Vanderbilt is the only private university in the SEC so there is a clearer picture than there is for the ACC that has 9 of 18 schools being private. The television and media contract delivers more to SEC schools because of the more lucrative nature of their football contract as compared to the ACC.

The per athlete share reflects the nature of the difference in the SEC v ACC run through the reality of the size of teams and that impact on per athlete payments.

The revenue sharing formula agreed to as part of the settlement that governs direct payments from universities to players follows the money, and the ACC v. SEC comparison checks out.

There is more money in football, so 16 of 18 schools are at the revenue sharing cap, and there are only 2 of 9 public universities in the ACC up against the cap (with lots more private universities and thus censored data).

Men’s basketball is a bigger source of revenue for the ACC (20.4% of total from men’s basketball v. 15.6% for the SEC). Keep in mind that this is based on a six year look back, and the past few years the ACC has been down as a whole, while the SEC has been up. Post season basketball success will show up over time in this approach if the basketball slide of the ACC continues.

For a school that knows the money is in football, but cares the most about basketball, one approach is to simply say we have $250,000 as a base for every basketball player per year, and then use the University-adjacent NIL third party to pay more for stars. This is a predictable way to try build a roster and have big money available for stars. Duke, UNC, Kentucky and others will be trying to do this. The only limiting factor is getting the amount of money into a BPACC that is needed to compete.

Bottom Line, Big Picture, Gut Check, Does This Make Sense?

I thrash back and forth with myself about all of this. To stay in the guise of wishy washy professor, here are my gut check answers, that I hold simultaneously:

The revenue sharing approach (direct pay from universities to players) is a pretty good market-based approach. It passes the conference and sport specific smell test.

This is crazy, why are we doing this? Let’s stop, we are a University.

Duke is a charter member of the ACC (1953) and big-time sports is part of our institutional DNA. Duke and UNC are not going to stop participating. and the North Carolina General Assembly has passed a law saying UNC and NC State cannot be in a different conference. People obviously care, a lot about college sports.

The number of early entrants (underclassmen declaring for the NBA draft) is lower this year than for some time. College players being paid nudges incentives for all but stars to stay in school and get paid.

Higher Education is having its financial model fully upended now, and here we are putting so much energy into working out how to pay plyers.

If we got rid of big-time sports, we might be giving up the only bipartisan thing that people seem to like about Duke, UNC and other universities—big time sports.

I do not blame the kids one bit. The system we had for a long time was economically unjust. And it stopped and now the changes are hard to control, because the money is big.

The Deloitte clearinghouse is a nice idea to try and keep outside NIL legitimate, competition good, etc. but the execution of it is fraught. I fear this to be a losing battle, and that the juice will not be worth the squeeze. I’d settle for complete transparency regarding how much each university spends via their BPACC and otherwise, and ruthless attempts to try and keep betting interests and those seeking to fix games away. Most importantly, full transparency will help us be honest with ourselves about what we are doing. For a professor whose first day at Duke University was 28 years ago today, being honest with ourselves seems particularly important.

This is a good piece, Don!